For many of us, especially those living in the "colonies", our introduction to the Hansom cab came as we first read the works of Dr John Watson about his sometime companion Sherlock Holmes, the greatest detective of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. This is neither the time nor the place to explore the relationship between the two men or their involvement with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the well known literary agent for John (or was it James?) Watson. Rather such speculation should be left to those pseudo-scientists who delight in the name of "Sherlockians." Ours is a more serious business, to consider that most famous mode of transportation in the Victorian Era, the Hansom cab.

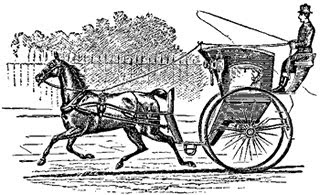

During Victoria's reign, two types of "hired" transport dominated the streets of London. The first of these was a four-wheeled vehicle, the Clarence or the "growler" (pictured left)which acquired its nickname as a result of the noise it made when driven over the cobblestoned streets. A closed, four-wheeled carriage, it was glass-fronted and seated four passengers in relative comfort. It was a popular vehicle holding more passengers and baggage than the hansom cab and for this reason was often found at railway stations. Indeed, so popular was it that as Mrs Beeton notes in 1861, "the family carriage of the day being a modified form of the clarence adapted for family use."

During Victoria's reign, two types of "hired" transport dominated the streets of London. The first of these was a four-wheeled vehicle, the Clarence or the "growler" (pictured left)which acquired its nickname as a result of the noise it made when driven over the cobblestoned streets. A closed, four-wheeled carriage, it was glass-fronted and seated four passengers in relative comfort. It was a popular vehicle holding more passengers and baggage than the hansom cab and for this reason was often found at railway stations. Indeed, so popular was it that as Mrs Beeton notes in 1861, "the family carriage of the day being a modified form of the clarence adapted for family use."

It was the two wheeled hansom cab, however, that was the most popular public vehicle of the century. Although named for its inventor, the coachbuilder Joseph Hansom (pictured right), the design of the cab which dominated the London streets was that of John Chapman. In many ways it was the ideal vehicle for

moving through the crowded London streets quickly. The body was light enough to be pulled by a single horse and with only two wheels and a low centre of gravity could safely turn on a sixpence. Speed, coupled with maneuverability meant that the hansom cab could steer through the traffic jams so common in later Victorian London.

moving through the crowded London streets quickly. The body was light enough to be pulled by a single horse and with only two wheels and a low centre of gravity could safely turn on a sixpence. Speed, coupled with maneuverability meant that the hansom cab could steer through the traffic jams so common in later Victorian London.The driver of the hansom cab sat on a raised seat above and behind the passengers compartment. Two passengers could ride with reasonable comfort in the cab and a third might be squeezed

in if necessary. Passengers spoke to and paid the driver through a trap-door in the roof which also provided a degree of security for the driver who had control of a lever used to release the doors once the fare had been paid. The reins used to control the horse at the front of the cab ran over the roof of the vehicle which meant that the only part of the horse visible to the driver was its head.

in if necessary. Passengers spoke to and paid the driver through a trap-door in the roof which also provided a degree of security for the driver who had control of a lever used to release the doors once the fare had been paid. The reins used to control the horse at the front of the cab ran over the roof of the vehicle which meant that the only part of the horse visible to the driver was its head.It is not surprising that our image of the Hansom cab is somewhat fogged by time. Comfortable, they were not, nor were they particularly clean. In the early days, with their open fronts, the passengers were likely to get wet if it rained or have to deal with whatever the horse's hooves threw up from the road. Later, they had folding half doors which protected the passengers' legs. Mr Udny Yule, in proposing a vote of thanks to a speaker at the Royal Statistical Society in 1936, took the ocassion to comment on London as he had known it as a boy. Among his observations was a comment on "giving unintended hospitality to a hungry flea picked up on some growler or hansom cab," which he went on to note "was not exceedingly rare." It was certainly a case for Keating's Powder, a well-known product advertised in the '80s with the lines: "Keating's Powder does the trick/Kills all Bugs and Fleas off quick".

Drivers of Hansom cabs were often before the courts for drunkeness and abusing or injuring their passengers or pedestrians. To cite only one example, from The Times of 12 April 1882.

At MARYLEBONE, ROBERT COOMBER, 38, hansom cab driver, was charged with being drunk and furiously driving his cab, thereby causing damage to the extent of £4 to another cab and seriously injuring Mrs. Elizabeth Griffin. ... On Monday night about half-past 11, the prisoner, who was intoxicated, was seen driving his cab at a very fast rate ... on the wrong side of the way. He was shouted to, but took no notice, and after going some 600 yards he came into collision with another cab, and the shaft of his cab struck Mrs. Griffin who, with her husband, was in the damaged vehicle. She was picked up senseless and was taken to a doctor's where it was found that she was seriously injured. During the night she only recovered consciousness for a few minutes. Her husband also received a severe shock.Small children playing in the streets were particularly vulnerable. Only six weeks later two little boys, one sixteen months old and the other four and a half years were killed by horse drawn vehicles; the latter by a hansom cab.

Although the Hansom Cab continued in use until well into the twentieth century, its popularity waned and within the first decade of the new century it was being reported that "'London's gondola,' the hansom cab, has had its day, and the future is with the taximotor."

What amounts to an official recognition of the fact is to be found in a new police regulation on the subject of cab whistles. Hitherto one blast has signified a call for a hansom, two blasts meant a four wheeler, or 'growler,' and three were required to summon a taximotor.But there are still those of us who believe, as the yellow fog settles over London, that we can hear the footsteps of Holmes and Watson as they race towards a Hansom and in the ghostly stillness we can still hear Holmes' strident voice, "Come, Watson, come. The game is afoot."

Now this is all changed by a regulation issued by the Chief Commissioner of Police and the 'taxi' takes the place of honor, the hansom going down, and the 'growler' being last in order. Henceforward one whistle summons a 'taxi.'

There are numerous tales which involve hansom cabs. Here are two you might find of interest.

"The Adventure of the Hansom Cab," by Robert Louis Stevenson is one of the stories in the compilation New Arabian Nights which can be downloaded by clicking here.

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, an Australian Novel (1886) by Fergus Hume can be downloaded by clicking here.

And of course, there are all those Sherlock Holmes stories!